Helen Lawrenson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

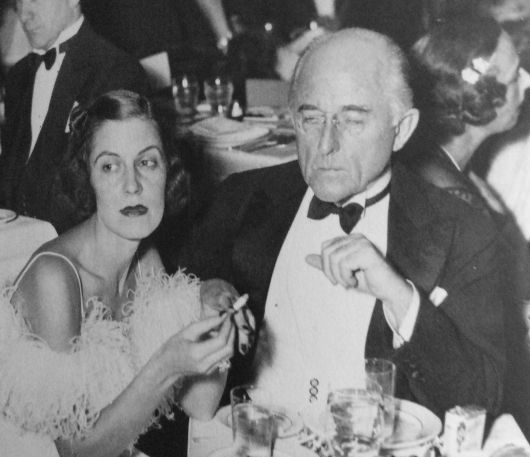

Helen Lawrenson (born Helen Strough Brown, October 1, 1907 – April 5, 1982),

was an American editor, writer and socialite who gained fame in the 1930s with her blunt descriptions of New York society. She made friends with great ease, many among the rich and famous, notably author

Helen Lawrenson (born Helen Strough Brown, October 1, 1907 – April 5, 1982),

was an American editor, writer and socialite who gained fame in the 1930s with her blunt descriptions of New York society. She made friends with great ease, many among the rich and famous, notably author

Available at Archive.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lawrenson, Helen 1907 births 1982 deaths 20th-century American women writers 20th-century American journalists Journalists from New York City American film critics American women film critics American women editors American socialites American autobiographers American women journalists People from Jefferson County, New York

Helen Lawrenson (born Helen Strough Brown, October 1, 1907 – April 5, 1982),

was an American editor, writer and socialite who gained fame in the 1930s with her blunt descriptions of New York society. She made friends with great ease, many among the rich and famous, notably author

Helen Lawrenson (born Helen Strough Brown, October 1, 1907 – April 5, 1982),

was an American editor, writer and socialite who gained fame in the 1930s with her blunt descriptions of New York society. She made friends with great ease, many among the rich and famous, notably author Clare Boothe Luce

Clare Boothe Luce ( Ann Clare Boothe; March 10, 1903 – October 9, 1987) was an American writer, politician, U.S. ambassador, and public conservative figure. A versatile author, she is best known for her 1936 hit play '' The Women'', which ha ...

and statesman Bernard Baruch.

At the height of the Great Depression, in the 1930s, she was an editor of '' Vanity Fair''. She later became notorious for an article called "Latins Are Lousy Lovers", published in '' Esquire'' in 1936. She supported herself by writing articles for the rest of her life.

Lawrenson's two autobiographies, ''Stranger at the Party'' and ''Whistling Girl'', are full of anecdotes and strong opinions – especially about New York society, politics left and right, and dense with anecdotes and vehement statements not easily corroborated.

Early life

Lawrenson was born on October 1, 1907 inLa Fargeville, New York

La Fargeville is a hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in the town of Orleans in Jefferson County, New York, United States. The population was 608 at the 2010 census. The hamlet is named after John Frederick La Farge, one of the early propr ...

, seven miles south of the Canadian border

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

, to Lloyd E. Brown and Helen Minerva Brown. She was not close to her parents. Her mother once confided to her she never wanted children, and had made several attempts to get rid of Helen as a foetus: hot mustard baths, enemas, riding horseback, and more. Lawrenson claims to have learned to read at three; her childhood was spent in voracious reading, with few friends, though as an adult, her friends were many.

In New York City for a year at age 7, she attended the Ethical Culture

The Ethical movement, also referred to as the Ethical Culture movement, Ethical Humanism or simply Ethical Culture, is an ethical, educational, and religious movement that is usually traced back to Felix Adler (1851–1933).

school. Then she was taken under the care of her maternal grandmother, who took her back to Syracuse, and exposed her to much culture. She got to hear Paderewski

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (; – 29 June 1941) was a Polish pianist and composer who became a spokesman for Polish independence. In 1919, he was the new nation's Prime Minister and foreign minister during which he signed the Treaty of Versail ...

and to see Pavlova dance and was awed, as well as various Shakespearean companies. She was largely supported by her grandmother, first at private school and then the elite Vassar College

Vassar College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Poughkeepsie, New York, United States. Founded in 1861 by Matthew Vassar, it was the second degree-granting institution of higher education for women in the United States, closely foll ...

for two years.

Career

Tiring of Vassar, she got jobs as a newspaper reporter in Syracuse, New York — two years on the ''Journal

A journal, from the Old French ''journal'' (meaning "daily"), may refer to:

*Bullet journal, a method of personal organization

*Diary, a record of what happened over the course of a day or other period

*Daybook, also known as a general journal, a ...

'', then two years when lured away to the ''Herald

A herald, or a herald of arms, is an officer of arms, ranking between pursuivant and king of arms. The title is commonly applied more broadly to all officers of arms.

Heralds were originally messengers sent by monarchs or noblemen to ...

'', a Hearst paper.

Lawrenson enjoyed the work greatly, and learned the trick of acting casual. "It was a matter of pride with us never to appear to be working." She interviewed, among others, Lindbergh, Admiral Byrd

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer and explorer. He was a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest honor for valor given by the United States, and was a pioneering American aviator, p ...

, Red Grange

Harold Edward "Red" Grange (June 13, 1903 – January 28, 1991), nicknamed "the Galloping Ghost" and "the Wheaton Iceman", was an American football halfback for the University of Illinois, the Chicago Bears, and the short-lived New York Yankees ...

, Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

, Al Jolson

Al Jolson (born Eizer Yoelson; June 9, 1886 – October 23, 1950) was a Lithuanian-American Jewish singer, comedian, actor, and vaudevillian. He was one of the United States' most famous and highest-paid stars of the 1920s, and was self-billed ...

(whom she idolized). She also loved reviewing burlesque shows in New York City.

"The life I managed to lead was an entertainingly dissipated caper", with heavy drinking in speakeasies

A speakeasy, also called a blind pig or blind tiger, is an illicit establishment that sells alcoholic beverages, or a retro style bar that replicates aspects of historical speakeasies.

Speakeasy bars came into prominence in the United States ...

, as it was illegal during Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

.

Remarkably, in 1932, at the depth of the Depression, she ascended to heights of comfort and prestige. She came to New York as an editor of ''Vanity Fair'', a fashionable magazine which maintained a frolicsome attitude as if the Depression did not exist. She describes the atmosphere at ''Vanity Fair'' as a happy one, largely because of editor Frank Crowninshield

Francis Welch Crowninshield (June 24, 1872 – December 28, 1947), better known as Frank or Crownie (''informal''), was an American journalist and art and theater critic best known for developing and editing the magazine ''Vanity Fair'' for 21 y ...

. Once a week, they were treated to a fancy lunch from the Savarin restaurant.

Lawrenson was a senior editor and film critic

Film criticism is the analysis and evaluation of films and the film medium. In general, film criticism can be divided into two categories: journalistic criticism that appears regularly in newspapers, magazines and other popular mass-media outl ...

at ''Vanity Fair'' from 1932 to 1935 and also wrote for ''Vogue

Vogue may refer to:

Business

* ''Vogue'' (magazine), a US fashion magazine

** British ''Vogue'', a British fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Arabia'', an Arab fashion magazine

** ''Vogue Australia'', an Australian fashion magazine

** ''Vogue China'', ...

'', '' Harper's Bazaar'', '' Look'', ''Esquire'' and '' Town & Country''. Lawrenson was the first woman to write for men's magazine ''Esquire''. Her first article, "Latins Are Lousy Lovers" (1936), initially published anonymously, in which she ridiculed machismo as “quantity rather than quality”, caused a sensation and was considered probably the “most notorious piece” in an ''Esquire'' collection from 1973. While married to her first husband, she published under the name Helen Brown Norden.

She attended lavish parties and dinners, in a high society of the rich, titled and entitled. According to Jane Fonda, once Roger Vadim

Roger Vadim Plemiannikov (; 26 January 1928 – 11 February 2000) was a French screenwriter, film director and producer, as well as an author, artist and occasional actor. His best-known works are visually lavish films with erotic qualities, su ...

asked Lawrenson "Do I look like Abraham Lincoln?" to which she replied "All I see is a guy with big ears and a hangdog face." According to Lawrenson, Jackie Kennedy

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis ( ; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was an American socialite, writer, photographer, and book editor who served as first lady of the United States from 1961 to 1963, as the wife of President John F. Kennedy. A po ...

was very aware of her husband's "hundreds of women". Lawrenson wrote an uncustomarily negative article about Julie Andrews, calling her background not "compatible with reticence and timidity".

She continued to support herself precariously by writing articles the rest of her life.

Communist spy

She was recruited as a spy once, which took her into danger inSouth America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

.

At Communist party headquarters on East 13th street, in 1938, she was given a spying assignment by a Venezuelan she knew only as "Ricky". Ricky told her to find out about canals in Chile, which had been used by the Germans in World War I. The trip was well publicized (her cover story was to write travel articles), but her experience was harrowing because of her own initiatives. Some of these initiatives nearly got her killed. In every city she tried to meet left-wing politicians. She was more than once fired upon in crowds, closely escaping death at least once. Her comments on American ambassadors in South America are scathing.

Personal life

Lawrenson did not shy away from seedier places. During Prohibition she found that when the speakeasies were closed, whorehouses kept serving liquor. She was associated with men such as Bernard Baruch, Rabbi Wise, andCondé Nast

Condé Nast () is a global mass media company founded in 1909 by Condé Montrose Nast, and owned by Advance Publications. Its headquarters are located at One World Trade Center in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan.

The company's media ...

.

She married three times. The third marriage resulted in a son, Kevin, and a daughter, Johanna. Her husbands were musician Heinz Norden (m. 1931, div. 1932), Venezuelan diplomat Louis López-Méndez (m. 1935, div. 1935) and finally union organizer Jack Lawrenson (co-founder of the National Maritime Union

The National Maritime Union (NMU) was an American labor union founded in May 1937. It affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in July 1937. After a failed merger with a different maritime group in 1988, the union merged wi ...

), her true love (m. 1940 until his death in November 1957). She had met Lawrenson in 1938. Their life was fraught with danger: "On one of our first dates he took me to a waterfront saloon that was the hangout of the shipowners' agents who had been offered money to kill or maim him. Several of the goons were there and the atmosphere was electric with tension and menace. Blissfully unaware of the cause, I had a wonderful time. I suppose the only reason we emerged unscathed was because Joe Kay, a seaman friend who accompanied us, although admittedly frightened, had the wit to tell the bartender that I was a member of District Attorney Dewey's staff, and the word was passed around."

According to Lawrenson, her husband was written out of the histories of the union by Joseph Curran

Joseph Curran (March 1, 1906 – August 14, 1981) was a merchant seaman and an American labor leader. He was founding president of the National Maritime Union (or NMU, now part of the Seafarers International Union of North America) from 1937 to ...

, the "vicious and undeserving winner" "who corrupted the union Jack built", and repeatedly tried to kill him. (Both Lawrenson and Curran had earlier been members of the Communist party, but Curran pretended not to have been.)

In her later life, she lived modestly, having to keep writing to support herself. She had repeatedly turned down marriage offers from Condé Nast, who remained an ally and friend until the end of his life.

Death

Lawrenson, 74, died on April 6, 1982, apparently suffering a heart-attack, after failing to show up for lunch with longtime agent Roz Cole and representatives of theSimon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster () is an American publishing company and a subsidiary of Paramount Global. It was founded in New York City on January 2, 1924 by Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster. As of 2016, Simon & Schuster was the third largest pu ...

publishing house. At the time, she was finishing up her first novel, Dance of Scorpions, which was published posthumously later that year.

References

Bibliography

* ''Stranger at the Party, a Memoir'' by Helen LawrensonAvailable at Archive.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lawrenson, Helen 1907 births 1982 deaths 20th-century American women writers 20th-century American journalists Journalists from New York City American film critics American women film critics American women editors American socialites American autobiographers American women journalists People from Jefferson County, New York